3.2 Complex Geometry- The Complex Plane

Complex numbers can be identified

with points in a cartesian plane by having $a +bi$ identified with the

point with coordinates $(a,b)$ or with position vectors by identifying

$a+bi$ with the vector $<a,b>$. With this identification $i$ is

identified with the point $(0,1)$ and $-i$ is identified with $(0,-1)$.

3.2.1 Complex Number Norm (Magnitude):

The norm of $z$ is defined by $|z| = |a+bi| = \sqrt{ a^2 +b^2}$

3.2.2 Polar Representation of $z$: ¤

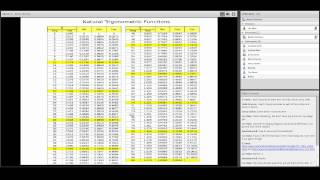

Using trigonometry we have the identification:

$$z = |z| \cos( \theta) + |z| \sin(\theta) i = |z|

[\cos( \theta) + \sin(\theta) i] = |z| cis( \theta) $$ where $a = \cos( \theta ), b = \sin(\theta)$.

$z$ is sometimes represented as an ordered pair $(|z|, \theta)$.

The angle $\theta$ determined by $z$ can be measured in degrees or

radians and restricted to be in a specific interval.

For example $\theta

\in [0,2 \pi)$ or $\theta \in (-\pi, \pi]$.

Thus the angle can be considered a function of $z$, called the argument of $z$: $Arg(z) =\theta$.

|

|