Martin Flashman's Courses

MATH 418 Complex Analysis Spring 2015

MWF 11:00 SH 002

Class Notes and Summaries

Week 1:

1-21: The first day of class was introductory.

The focus of the course will be to understand complex numbers,

functions of complex numbers, and the derivative, integral and series

calculi for complex functions.

Math 418 covers the calculus of complex numbers and complex number valued

functions of one complex variable.

Key theorems we will examine will involve continuity,

differentiability, and integrability. The first coherent and

somewhat successful presentation of calculus for complex functions was by Cauchy in the

early 19th century- about 150 years after the works of Newton and

Leibniz.

We will use a working definition for what a real number is: a real

number is any number that can be represented as a possibly infinite

decimal (positive or negative) or that can be thought of a the

measure of a length of a line segment either to one side or the

other of a specified point on on a given line an a specific unit for

measurement.

Details of the syllabus will be discussed further on Friday.

1-23 [More details to follow.]

The organization of the course:

details like tests, homework, etc. as described in the main

course page.

In the discussion reference was made to Polya's :

How to Solve It...

Polya describes 4 Phases of Problem Solving

1. Understand the problem.

2. See connections to devise a plan.

3. Carry out the plan.

4. Look back. Reflect on the process and results.

It is the first phase that is usually not recognized as being

essential. there is usually more to understand than is apparent.

Also mentioned were other texts in Complex Analysis : See Moodle lists.

On Proofs:

- Daniel Solow's work was mentioned with on-line references on home page.

- How to Read and Do Proofs by D.Solow

- The Keys to Advanced Mathematics by D. Solow

- Polya's :

How to Solve It... available on line:

https://notendur.hi.is/hei2/teaching/Polya_HowToSolveIt.pdf

Start work on Complex Numbers:

Reading through class as start on how to: SOS 1.10 (?); 1,12; 1.53; 1.54; 1.55a; 1.56a.;1.59

Algebra and geometry problems from (i) SOS 1.53-1.74 (ii) Aben Chapter 2 (3?)

Week 2

1-26: Continue work on Complex Numbers.

Possible pr/exercises to do in class: SOS 1.10 (?); 1,12; 1.53; 1.54; 1.55a; 1.56a.;1.59

Algebra and geometry problems from (i) SOS 1.53-1.74 (ii) Aben Chapter 2 (3?)

Class Problem work notes from "secretary's report".:

1.72.

Find an equation for (a) a circle of radius 2 with center at (-3, 4),

(b) an ellipse with foci at (0, 2) and (0, -2) whose major axis has

length 10.

(a) Let $z=x+iy$. We have a radius of 2, center at (-3,4), or $-3+4i$

Cartesian form: $(x+3)^2+(y-4)^2=4$

But this doesn't really answer this question the way we want it to...

Complex form: if the center is at $-3+4i$, and we want $r=2$, we are

saying that the distance away from $z$ to $3+4i$ is $2$. Recall that modulus of

$z$, $|z|$ measures distance/length of vector.

So, the equation is $|z-(-3+4i)|=2$

(b) foci (0,2) and (0,-2) are $2i$ and $-2i$, respectively

Recall

from the definition of an ellipse that the total of the distances from the foci

to a point on the ellipse will be equal to the length of the major axis.

So, $|z-(-2i)|+|z-2i|=10$

Note:

$|z|$ is a function that takes a complex number to a real numbers and

is not one to one. (Two different z values will map to the same real

number.)

Look at technology for visualizing complex numbers:

Geogebra -

1-28: Continue foundational work on Complex Numbers.

Start on how to: SOS 1.7(a); 1.19; 1,12; 1.22;1.43; 1.44; 1.55a; 1.56a.;1.59

Algebra and geometry problems from (i) SOS 1.75-1.99 (ii) Aben Chapter 2 (3?)

CORRECTION/NOTE from discussion of 1-26 : $ |z|^2 = z \cdot \overline z$.where $\overline {a+bi} = a - bi$.

Notes from "secretary's report":

1.82 Show that $2+i = e^{i \arctan(\frac 12)}$

Solution: If

$ z = a+bi$, we know that $|z| = \sqrt {a^2 + b^2}$. Also, we know that $\theta =

\arctan(\frac ba)$. Lastly, we know $z = a+bi = |z|e^{i \theta}$. Hence $|z| =

\sqrt{2^2 + 1^2} = \sqrt(5); \theta = \arctan(\frac 12)$. Therefore $z = 2+i = \sqrt 5 e^{i \arctan(\frac 12)}$.

We also "proved" Euler's formula, $e^{i \theta} = \cos(\theta)+i \sin( \theta)$, by

using the taylor series expansion of all three terms.

Since all three

series are absolutely convergent, we can rearrange the left side in such

a

way that $e^{i \theta} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(i

\theta)^n}{n!} = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^k

\theta^{2k}}{(2k)!} + \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^k i

\theta^{2k+1}}{(2k+1)!} = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^k

\theta^{2k}}{(2k)!} +

i \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^k \theta^{2k+1}}{(2k+1)!}

= \cos(

\theta)+i \sin( \theta)$.

1.97 a) Find the roots of $z^4+81 = 0$.

Solution:

Note if $z$ is a root of the equation then $z^4=-81 = 81 e^{\pi i}$.

Using Euler's formula with $z = re^{i \theta}$, we have $r^4 = 81$,

hence $r = 3$. Also using

$z^n

= r^n(cos( (n \theta ) +isin( (n \theta ))$ with $n = 4$ we use the periodicity of the sine and cosine to conclude that

$4\theta = \pi, 3\pi, 5\pi,7\pi$. Therefore by solving and plugging

the $\theta$

values back into the sine and cosine functions we obtain the roots

are $z =3(\pm \frac{\sqrt 2}2 \pm \frac {\sqrt 2}2 i )$.

1-30 Notes from "secretary's report".

1.88 a) Prove that $r_1e^{i \theta_1} + r_2e^{i \theta_2} = r_3e^{i \theta_3}$

where

$r_3= \sqrt{r_1^2+r_2^2+2r_1r_2cos( \theta_1 - \theta_2)} $

and $\theta_3= \arctan(\frac{r_1sin( \theta_1)+r_2sin(

\theta_2)}{r_1cos( \theta_1)+r_2cos( \theta_2}))$.

Solution: We

know that a complex number, $a+bi$ can be written in the form $

re^{i \theta}$ where $ r = \sqrt{a^2+b^2}$ and $\theta = |arctan (\frac ba)$. If

we give ourselves 2 arbitrary complex numbers, $z_1=a_1+b_1i $and $ z_2= a_2+b_2i$,

we can say that the sum of two complex numbers amounts to complex

number $z_3= a_1+b_1i +a_2+b_2i= (a_1+a_2) +i(b_1+b_2)$.

Calculating the radius for $z_3$, we have $r_3 = \sqrt{(a_1+a_2)^2 +(b_1+b_2)^2)}$.

Recognizing

the "dot product" of the vectors $<a_1,b_1>\cdot<a_2,b_2> =

a_1a_2+b_1b_2 $, We see that $a_1a_2+b_1b_2 = r_1r_2cos( \theta_1

- \theta_2)$, and so substituting

into our modulus for $z_3$, we have $r_3= \sqrt{r_1^2+r_2^2+2r_1r_2cos(

\theta_1 - \theta_2)} $ as desired.

To

show that $\theta_3= arctan(((r_1)sin( \theta_1)+(r_2)sin(

\theta_2))/((r_1)cos( \theta_1)+(r_2)cos( \theta_2)))$, we know that

imaginary part for $z_3$ is given by $r_1sin( \theta_1)+ r_2sin(

\theta_2)$.

The

real part of $z_3$ is given by the sum of $r_1cos( \theta_1)$ and

$r_2cos( \theta_2)$. Taking the arctangent of these two components yields the

desired answer, $\theta_3= \arctan(\frac{r_1sin( \theta_1)+r_2sin( \theta_2)}{r_1cos( \theta_1)+r_2cos( \theta_2}))$.

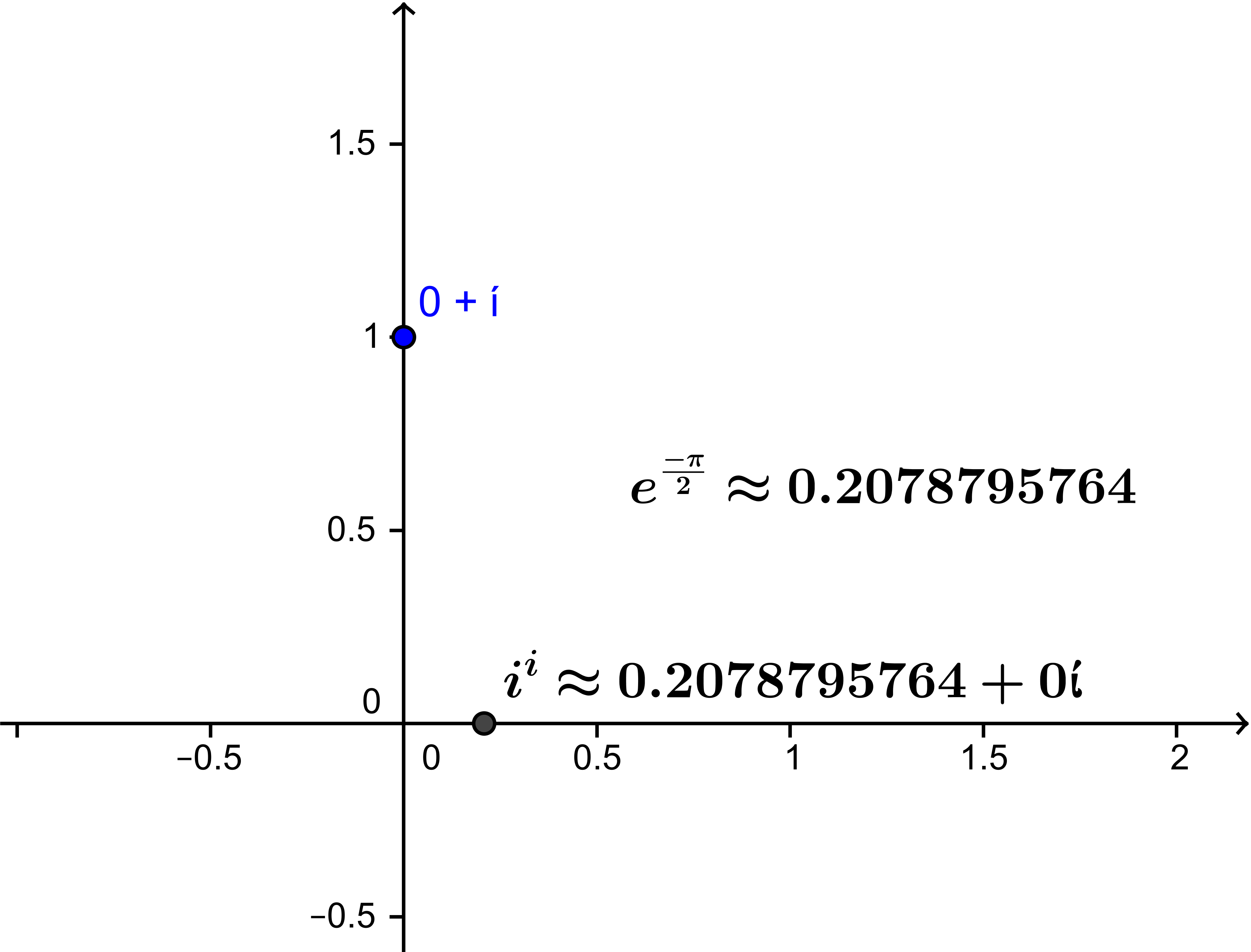

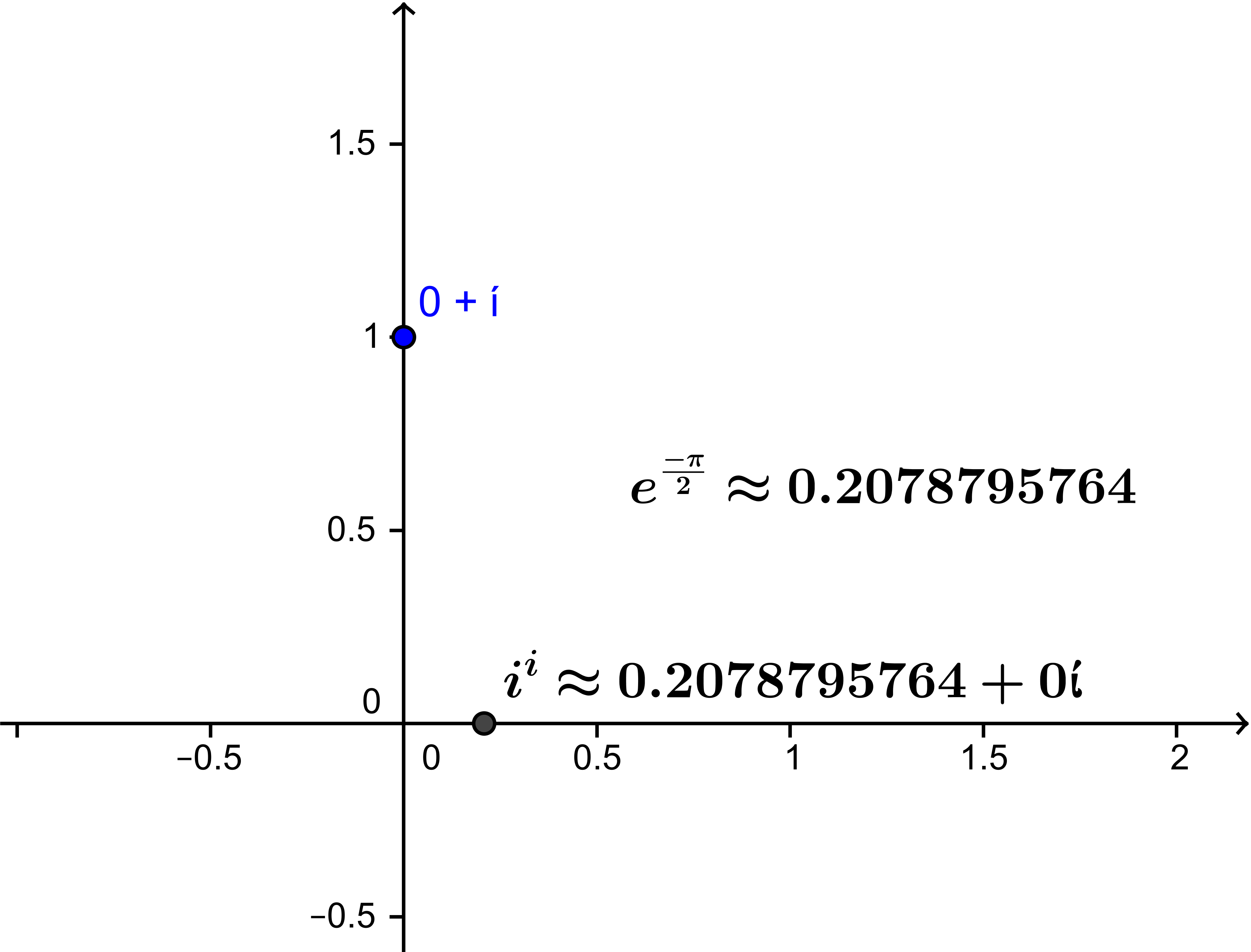

Later in the class, a student posed a question: what is the value of $i^i$? Turns out it’s a real number(no pun intended)!

Solution: We use the fact that $i = e^{i \frac {\pi}2}$

We consider $i^i$ by applying exponent rules and we have $i^i = {(e^{i \frac{\pi}2 }})^i =e^{i\cdot i\frac{\pi}2}$

so.... $i^i = e^{-\frac{\pi}2} \approx 0.2078$. This was verified using GeoGebra.

Week 3

2-2: Solving Polynomial Equations-The Rational Root Theorem works for complex with polynomials with integer coefficients:

Take the ratio of the factors of the first and last coefficients and

proceed by trial and error. Long division is require.

Problem

1.101: Find the roots of $p(z)=z^5-2z^4-z^3+6z-4$.

Solution: Using the rational

root test, the possible roots are ±1, ±2, ±4. Using substitution, we

know that $p(1)=p(2)=0$.

So $q(z)=(z-1)(z-2)=z^2-3z+2$. Now we divide $p(z)$ by $q(z)$ to get $r(z)=z^3+z^2-2$. Hence,

$r(z)∙q(z)=p(z)$, and we have to find the roots of $r(z)$, which are $1, -1+i$ and $-1-i$.

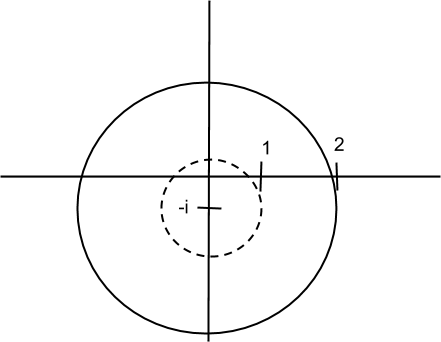

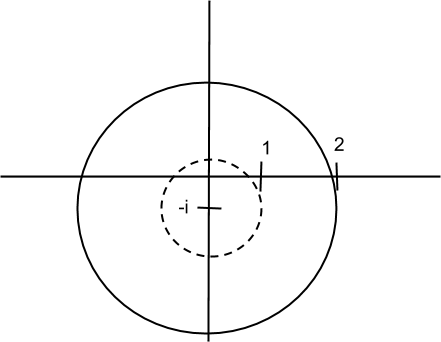

Region of complex inequality. In particular we looked at the “annulus” or “ring”.

$R_1<|z-(a+bi)|<R_2$ centered at $ a+bi$.

$1<|z+i|≤2$ is the region below in between the dashed-line circle and the solid-line circle.

2-4: Complex exponentials. $e^z=e^{x+iy}=e^xe^{iy}$.

Proving trigonometric identities using De Moivre’s theorem

Problem 1.93. Prove $\frac {\sin (4\theta)}{\sin (\theta)}= 8\cos^3(\theta) - 4 \cos(\theta) = 2\ cos(3\theta) + 2 \cos(\theta)$

Idea: $\sin(4\theta) = Im \{ ( \cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta))^4\}$. This

turns out to have a common factor of $\sin(\theta)$.

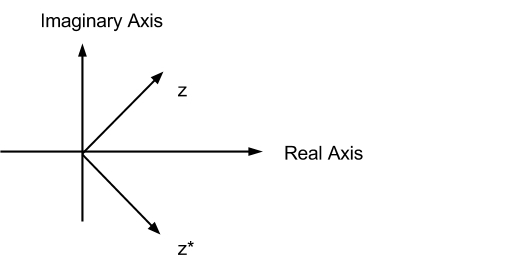

2-6: Geometric interpretation of complex conjugate. $ z = x+ yi$ , $\overline z = x - yi$. $\overline z$ is denoted in the figure by $z^*$.

It's a reflection over the Real Axis

Problem 1.133. Let $P(z)$ be any polynomial with real coefficients. Prove $\overline {P(z)} =P( \overline z)$ assuming coefficients are real.

Idea: Use the facts that $\overline{z\cdot w} = \overline z \cdot

\overline w$, $\overline{z + w} = \overline z+\overline w$ and $\overline a =

a$ when $a$ is a real number.

Matrix interpretation of complex numbers

$1 : \left( \begin{array}{cc}1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1

\end{array} \right) \\ i : \left( \begin{array}{cc}0 & 1 \\-1

& 0 \end{array} \right)$

$a+bi = \left( \begin{array}{cc}

a & b \\

-b & a \end{array} \right) \\ |a +bi| = det \left( \begin{array}{cc}

a & b \\ -b & a \end{array} \right) $

Problem 2.50 (d) $f(z) =\frac{ z+2}{2z-1}$. Find values of $z$ such that $f(z) = z$.

Solution: $\frac{ z+2}{2z-1} = z$ so $z+2 = z \cdot (2z-1) = 2z^2 -z$.

So $2z^2 -2z -2 = 0$ or $z^2 -z -1 = 0$ and by the quadratic

formula $ z =\frac{ 1 \pm \sqrt{1 + 4 }}2 =\frac{ 1 \pm \sqrt 5}2 $. Checked with winplot:

Week 4

February 9th - 11th

On February 9th and early February 11th we worked on an example from the

text and studied some of the properties of the function provided using

the interactive complex mapping diagram.

The function we studied is as follows:

$f(z) = z(2 - z) = (x + iy)(2 - (x + iy))$ assuming $z = x + iy$

After smearing a little complex algebra around, we attained the real and

complex parts and expressed them as functions of $x$ and $y$ as

follows:

$f(z) = x(2 - x) + y^2 + i((2y - xy) - xy)$

which yields

$u(x,y) = 2x - x^2 + y^2$ and $v(x,y) = 2y - 2xy$

Surprisingly, the real and imaginary parts of $f(z)$ satisfy the

Cauchy-Riemman Condition which is a necessary condition for

differentiability of complex functions. Observe:

$\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = 2 - 2x$

$\frac{\partial v}{\partial y} = 2 - 2x = \frac{\partial u}{\partial x}$

$\frac{\partial u}{\partial y} = 2y$

$\frac{\partial v}{\partial x} = -2y = -\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}$

You may study the function's properties using the complex mapping diagram found at:

We then looked at an example from the SOS pr/exercises where we showed the following:

All of the roots of $cos(z) = a$, where $-1 \leq a \leq 1$, are real.

Our immediate goal was to show that $Im\{ z \} = 0$.

This was done by expressing $cos(z)$ in terms of exponentials so:

Assume $cos(z) = a$, where $-1 \leq a \leq 1$. Then

$cos(z) = \frac{e^{iz} + e^{-iz}}{2}= a$

$\iff \frac{e^{iz} + e^{-iz}}{2} = a$

$\iff e^{iz} + e^{-iz} = 2a$

$\iff e^{iz} + \frac{1}{e^{iz}} = 2a$

$\iff(e^{iz})^2 + 1 = 2a e^{iz}$

$\iff(e^{iz})^2 - 2a(e^{iz}) + 1 = 0$

$\Rightarrow e^{iz} = a \pm \sqrt{a^2 -1}$

$\iff e^{-y}e^{ix} = a \pm i\sqrt{1 - a^2}$ assuming $z = x + iy$

$\Rightarrow|e^{-y}e^{ix}| = \sqrt{a^2 + 1 - a^2}$

$\iff e^{-y} = \sqrt1 = 1$ which happens only when $y = 0$

Thus $Im\{ z \} = 0$, and $z = x$, a real number.

Thus all of the roots of $cos(z) = a$, where $-1 \leq a \leq 1$, are real.

We ended lecture on Wednesday studying the geometric properties of basic functions on the $W$ - plane.

Using Winplot we looked at the most basic function:

$w = f(z) = z +a + ib $

Animating on $a$ and keeping $b$ constant makes the image of any point

on the $z$ - plane shift either left or right depending on the sign of

$a$. Similarly, animating on $b$ and keeping $a$ constant makes the

image of any point on the $z$ - plane shift either up or down depending

on the sign of $b$.

We next looked at the function:

$w = f(z) = z \cdot (a + ib)= z \cdot\rho e^{\theta i}$

Animating on $\rho$ "magnifies" the image of a set of points on the $z$ -

plane, while animating on $\theta$ rotates the image of a set of points

on the $z$ - plane depending on the angle $\theta$ of $(a + ib)$.

2-13

Example for HW Problem 2.83:

$f(z) = z^3 = (x+iy)^3 = x^3+3x^2iy+3x(iy)^2+(iy)^3 = x^3-3xy^2+(3x^2y-y^3)i$

$u(x,y) = x^3-3xy^2$

$v(x,y) = 3x^2y-y^3$

$\frac{du}{dx} = 3x^2-3y^2$

$\frac{du}{dy} = -6xy$

$\frac{dv}{dx} = 6xy$

$\frac{dv}{dy} = 3x^2-3y^2$

Note that $\frac{du}{dy}$ and $\frac{dv}{dx}$ are of opposite sign, but this is not always the case.

F$(z) = z = x-iy$

$\frac{du}{dx} = 1$

$\frac{du}{dy} = 0$

$\frac{dv}{dx} = 0$

$\frac{dv}{dy} = -1$

We then discussed the

general way that a derivative is found with linear functions, and how

this relates to finding derivatives of complex functions.

Linear function example for a real valued function:

$f(2) = 5$, $f(3) = 7$

What's the slope?

$\frac{f(3)-f(2)}{3-2} = \frac{7-5}{1} = 2$

$f(x) = 7+2(x-3) = 7+2x-6 = 2x+1$

Complex linear function example:

$f(1+i) = 2+i$, $f(1-i) = 1+i$

"Slope": $\frac{f(1+i)-f(1-i)}{(1+i)-(1-i)} = \frac{(2+i)-(1+i)}{1+i-1+i} = \frac{1}{2i} = \frac{-1}{2}i$

$f(z) = (2+i)+ \frac{-1}{2}i(z-(1+i)) = 2+i-\frac{1}{2}iz+\frac{1}{2}i-\frac{1}{2} = \frac{3}{2}+\frac{3}{2}i-\frac{1}{2}iz$

Check: $f(1-i) = 2+i+\frac{-1}{2}i(1-i-1-i) = 2+i-\frac{1}{2}i(-2i) = 2+i-1 = 1+i$

The term $\frac{-1}{2}iz$ serves as the rotation

factor. Any vector z is first cut in half and rotated 90 degrees

clockwise around the point $2+i$.

We then went to

An example: Using the definition of complex number derivatives for the function $f(z) = z^3$,

find $f'(z)$ when $z = 1+i$

Step 1: Evaluate

$f(z) = z^3$

$f(1+i) = (1+i)^3$

$f(1+i)$ has a length of $\sqrt{2}$ and angle

$\frac{\pi}{4}$, while $(1+i)^3$ has length $\sqrt{2^3}$ and angle

$\frac{3\pi}{4}$.

Step 2: Find the difference of the function values at $z$ and $1+i$.

$f(z)-f(1+i) = z^3-(1+i)^3$

Step 3: Divide:

$\frac{f(z)-f(1+i)}{z-(1+i)} = \frac{z^3-(1+i)^3}{z-(1+i)} = z^2+z(1+i)+(1+i)^2$, where $z \neq (1+i)$.

This solution holds from the rule of factoring cubic

polynomials for real number polynomials, since this rule works the same

for complex number polynomials

This is because the complex numbers and the real numbers are both "fields"..

Step 4: Think

Think about $z$ approaching $1+i$

As $z \to 1+i$ , we see that

$\frac{f(z)-f(1+i)}{z-(1+i)}= z^2+z(1+i)+(1+i)^2 \to 3(1+i)^2 = f'(1+i)$

There are two equivalent ways to define the complex derivative of

$w=f(z)$ at $z=z_0$, denoted $f'(z_0)$ or $\frac {dw}{dz}|_{z=z_0}$:

1: $\lim_{z → z_0} \frac{f(z)-f(z_0)}{z-z_0} = f'(z_0)$

2: $z-z_0 = \Delta z, \lim_{\Delta z \to 0} \frac{f(z_0+\Delta z)-f(z_0)}{\Delta z} = f'(z_0)$

Week 5

Notes: 2/16/2015 and 2/18/2015

Suppose $f(z)=u(x,y)+iv(x,y)$

$lim_{∆z →0}\frac{f(z+ ∆z)-f(z)}{∆z}$ ; Assumption: $f(z)$ has a derivative at $z$.

Assume $∆y=0$ then: $lim_{∆x→0}\frac{u(x+ ∆x,y)+iv(x+ ∆x,y)-u(x,y)-iv(x,y)}{∆x}$

$= ∂u/∂x+i ∂v/∂x$

Assume $∆x=0$: $lim_{∆y→0}\frac{u(x,y+ ∆y)+iv(x,y+ ∆y)-u(x,y)-iv(x,y)}{i∆y}$

$ = 1/i(∂u/∂y+i ∂v/∂y)$

$= (i/i)(1/i)(∂u/∂y+i ∂v/∂y)$

$= ∂v/∂y-i ∂u/∂y$.

Equate the real and imaginary components and we have the Cauchy-Riemann Equations!

$∂u/∂x= ∂v/∂y , ∂u/∂y= -∂v/∂x$

Example: $f(z)= 3z$,when $z\ne1$

$f(z)= 7$, when $z=1$.

Limits: we don’t care what actually happens at the point $z_0,$ only when near to $z_0$.

Notation: $D_δ={ z∶0< |z-1|< δ}$

Goal: be close to the target number

Find a way to describe $f(z)$ being close to $3$

Example: How do we make $f(z)$ Within $0.1$ of $3$.

|$f(z)- 3|< 0.1$

Find a set of $z$'s in the domain that satisfies closeness to $1$ ($\ne 1$)

We want $|3z- 3|< 0.1$.

or $|3(z- 1)|< 0.1$

that is, $3|z- 1|< 0.1$

so we want$ z-1|<\frac{0.1}3 ≈.03333333333333333333…$

Choose $\delta = 0.03$

Then if $0<|z- 1|< \delta$, then $f(z) – 3 = 3(z-1)$

So $|f(z)- 3|=3|z- 1|<3\delta = 0.09< 0.1$.

If you wanted to be within $0.01$ of $3$, I can find a deleted neighborhood of 1 with $\delta = 0.003$ where

if $0<|z- 1|< \delta$, then $f(z) – 3 = 3(z-1)$

So $|f(z)- 3|=3|z- 1|<3\delta = 0.009< 0.01$.

What about a tiny $\epsilon >0$?

Find a way to describe $f(z)$ being close to $3$ within $ε$ of $3$.

Given any $ε>0$-- so ...

Choose any $ε*>0$ (a fixed, specific $\epsilon$.)

Let $\delta = \frac{ε*}3$.

Then consider $z$ where $0< |z- 1|< \delta$.

Then $f(z) = 3z$

$f(z) – 3 = 3z – 3$

$ = 3(z-1)$

and sp $|f(z)- 3|=3|z- 1|<3\delta = 3 \cdot \frac{\epsilon *}3< \epsilon *$.

So $\lim_{z \to 1}f(z)= 3$.

2-20 SOS: Problem 2.89 (a) Show $lim_{z \to i} z^2+2z = 2i-1$.

Solution: Suppose $ \epsilon >0$.

We need to find $\delta >0$ so that

if $0<|z-i|<\delta$ then $|z^2+2z -(2i-1)| <\epsilon$.

Note that $|z^2+2z -(2i-1)| = |z^2- i^2 +2z -2i| = |(z+i)(z-i) +2 (z-i)| =|z+i+2||z-i|< |z+i+2| \delta$.

Since we can choose $\delta<1$ ,

we can show using the triangle inequality that $|z+i+2|=|z-i+2i+2| \le

|z-i|+|2i+2| <\delta + 3<4$. So $|z^2+2z -(2i-1)| < 4\delta$.

So we want $ \delta$ so that $4\delta < \epsilon$.

So choose $\delta = min\{ \epsilon/4 ,1/2\}$, and we have

$|z^2+2z -(2i-1)|< 4\delta \le 4 \epsilon/4 = \epsilon$.

Check with some GeoGebra examples on http://web.geogebra.org/app/?id=TBwX2yZs

Other discussion:

Consider $f(z) = \frac 1{z-i}$ and the definition of a "domain" for the

complex plane as an open and connected set of complex numbers.

The conventional domain of this function would be $D = \{z : z \ne i\}$

A set $O$ is defined as "open" if and only if for any $z_0 \in O$ there is a $delta \gt 0$ where$\{z:|z- z_0| \lt \delta \} \subset O$

With this definition one can show that $D$ is an open set.

Outline: Choose $z_0 \in D$. let $\delta = \frac{|z_0 -i|}2$. Then it

can be shown that $i \notin \{z:|z- z_0| \lt \delta \}$ we have $\{z:|z-

z_0| \lt \delta \} \subset D$ which shows $D$ is an open set.

For the concept of connected we can use a provisional definition that an open set $O$ is connected if given any two numbers in $O$, $w_1$ and $zw2$, there is a set of line segments in $O$ that "connect" the two numbers.

It was illustrated how the set $D$ is connected.

Proposition: If $S = \{ z_1, z_2, ...z_n\}$ is a finite set of complex numbers then $D = C - S$ is an open connected set.

Proof Plan: For $z_0 \in D$ let $\delta = \frac 12 \min \{|z_0-z_k|, k = 1, ... ,n\}$.

For any two numbers in $D$, $w_1$ and $w_2$ ,there is a set of line

segments that "connect" the two numbers while avoiding $S$, so the

segments are in $D$.

Final example: The set $S = \{z : z \ne \frac ik, k = 1,2,3,...\}$ is not an open set.

Discussion: Consider $z=0 \in S$. For any $\delta \gt 0$ there is a

number $k* \gt \frac 1{ \delta}$ so $|\frac ik | = \frac 1k \lt

\delta$ and thus there is no $\delta \gt 0$ where $\{z:|z-0| \lt \delta

\} \subset S$.

Week 6

Topology/Geometry of the Domain

Definitions

Open Sets: A set $O$ is open if (and only if)

for all $z_0 \in O$, there is a number $\delta > 0$ so that

$\{ z :| z - z_0| < \delta \}\subset O$.

Closed Sets: A set $S$ is closed

if the complementary set $S^c = \{z : z \notin S \}$ is an

open set. In

other words: The set $S$ is closed if for any $z_0 \notin

S$, there is a number $\delta > 0$ so that $\{ z :| z - z_0|

< \delta \}\subset S^c$. Stated in a direct way: $S$ is a closed set

if (and only if) whenever $z_0 \in S$ and $\delta > 0$

either $\{ z :| z - z_0| < \delta \}\subset S $ or for any number

$\delta > 0$ , $\{ z :| z - z_0| < \delta \}$ contains an

element $z_* \in S$ and

$z' \notin S$.

Connected Sets. An open set S is said to be connected if any two

points of the set can be joined by a path consisting of straight line

segments (i.e., a polygonal path) all points of which are in S.

Bounded Sets: The magnitude of all elements of a bounded set are smaller or larger than some given number.  Geometrically:

Geometrically:

Boundaries: The boundary of a set, $S$, denoted $\partial S$ is

given by those points which are surrounded by both points within and

outside of the set, that is, $z_0 \in \partial S$

if and only if for any number $\delta > 0$ , $\{ z :| z - z_0|

< \delta \}$ contains an element $z_* \in S$ and $z' \notin

S$.

Compact Set: A compact set is a set that is both closed and bounded.

Functions

2 main types of functions:

● Linear; of the form $f(z) = az + b$ where $a,b ϵ C $

● Mobius transformation; of the form $f(z) =\frac {az+b}{cz+d}$ where $a,b,c,d ϵ C$.

Functions transform the complex $z$ plane to the complex $w$ plane, where $w = f(z)$.

Three main notions about functions: Limits, Continuity, and Differentiability

Limits

The number $L$ is the limit of $f(z)$ as $z$ approaches $z_0$, written

as $\lim_{z→z_0} f(z) = L$, if for some small positive number $\epsilon

\gt 0$ we can find some small positive number $\delta \gt 0$ such

that $|𝑓(𝑧)−𝐿 |<\epsilon$ whenever $0 < |𝑧−𝑧_0| \lt

\delta$..

The limit must be independent of the manner in which $z$ approaches $z_0$.

Continuity

A function is said to be continuous at $z_0$ if $\lim_{z→z_0}f(z) = f(z_0)$. This implies the following three conditions:

1. $lim_{z→z_0} f(z) = L$ must exist

2. $f(z_0)$ must exist

3. $L = f(z_0)$.

Derivatives

The derivative of a single valued function, $f(z)$, in some domain of the complex $z$ plane is defined by:

$𝑓′(𝑧) = 𝑙𝑖𝑚_{\Delta z→0}]\frac { 𝑓(𝑧+𝛥𝑧)−𝑓(𝑧)}{ 𝛥𝑧 } $

provided that the limit exists independent of the manner in which $∆z$

goes to $0$. $f$ is said to be differentiable at $z$ if this is the

case.

A necessary condition for $f(z)$ to be differentiable at all points in a region is to satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations:

$\frac {\partial u}{\partial x} = \frac {\partial

v}{\partial y}$ and $\frac {\partial u}{\partial y} = -\frac {\partial

v}{\partial x}$

where $u$ and $v$ are respectively the real and imaginary parts of the transformation $f(z)$.

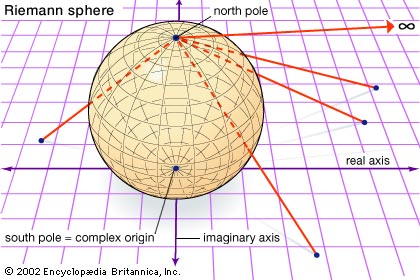

The Real Projective Line:

Every point on the real number line gets associated with a point on a

unit circle. -infinity and +infinity get mapped to the “north” pole of

the circle which is refer as to the point at infinity. Visually:

The analog of the Cartesian plane for the Real Projective line is the torus.

A similar construction attaches a single point at infinity to the complex numbers creating the "Riemann sphere."

2-27

Compactness in the Complex plane.

Definition: A subset $K$ of the complex numbers is called compact if $K$ is closed and bounded.

Theorem : Heine- Borel. (Not proven here- see a real analysis or advance calculus course, e.g Calculus on Manifolds by M. Spivak.)

$K$ is a compact set if and only if for any family of open sets $\{U_{\alpha}\}$ with $\alpha \in I$, $ I$ an indexing set for the family of sets, with the property that $K \subset \bigcup U_{\alpha} $.

then there is a finite collection of the $

U_{\alpha}$, which we can denote $\{ U_1, U_2, U_3, ..., U_n\}$ where

$K \subset \bigcup U_j $.

Compactness and continuous functions.

Theorem: Suppose $f$ is a continuous function on a domain $D$ and $K$ is a compact subset of $D$. Let $K' = f(K)$. Then $K'$ is compact.

Proof: Basic outline using the topological characterization of compact related to open covers.

Suppose $U'_{\alpha}$ is a family of open sets with $\alpha \in I$, $ I$

an indexing set for the family of sets, where $K' \subset \bigcup

U'_{\alpha}$.

Let $U_{\alpha}= f^{-1}(U'_{\alpha})$.

Since $f$ is a continuous function, each $U_{\alpha}$ is an open set and $K \subset \bigcup U_{\alpha}$.

Now since $K$ is compact, there is a finite collection of the $

U_{\alpha}$, which we can denote $\{ U_1, U_2, U_3, ..., U_n\}$ where $K

\subset \bigcup U_j$.

Now consider the corresponding family of sets, $\{ U'_1, U'_2, U'_3, ..., U'_n\}$.

For any $w' \in K'$, $w' = f(z)$ for some $z \in K$. But we have $z \in

U_j$ for some $j$, so $w' = f(z) \in U'_j$. Thus if $w' \in K' = f(K)$,

then $w' \in \bigcup U_j '$, so $K' \subset \bigcup U'_j$ for a finite

number of the original $U'_{\alpha}$. Thus $K'$ has been shown to be

compact. EOP.

Week 7 [ Notes are missing :( ]

Week 8

3-09

We began the lecture today by observing the following properties:

$e^{\pi i} = cos \pi + i sin \pi = -1$

$e^{-\pi i} = cos (-\pi) + i sin (-\pi) = -1$

so, $log(-1) = ln(-1) = \pi i$ or $-\pi i$

where $ln(z)$ is not continuous at any negative real values.

Observe:

Given $w = e^{x+iy}$, $ln(w) = x + iy + 2\pi ki$, where $2\pi ki$ defines periodicity.

We looked at two ways to interpret moving from $e \to -1$ in the $w$

plane : counterclockwise through upper half plane or clockwise

through the lower half plane.

$e \to -1$ in the image counterclockwise goes from $1 \to \pi i$ in the domain.

$e \to -1$ in the image clockwise goes to $1 \to -\pi i$ in the domain.

The mapping rotates around from $1$ to $\pi i$ and from $1$ to $-\pi i$

forming a continuous sheet (similar to $arctan(z)$ at $z =

\frac{-\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}$)

(Flashman may want to add a little extra here concerning the spiraling Riemann surface [see solved exercise 2.15]).

Multi-valued function with sheets is continuous, single-valued (just $1$ to $\pi i$ and $1$ to $-\pi$ i) is not?

3-11

Today we looked at the following mapping:

$w=(z) = \frac{3+z}{2-z}$

Observe that the function is doing some inversion.

Note that at $z = 0, 1, i$, and $\infty$

$f(0) = \frac{3}{2}$, $f(1) = 4$

$f(i) = \frac{3+i}{2-i} = \frac{(3+i)(2+i)}{5} = \frac{5+5i}{5} = 1+i$, and

$\lim_{z \to \infty}f(z) = \lim_{z \to 0} f(\frac{1}{z}) = \lim_{z \to

0} \frac{3+\frac{1}{z}}{2-\frac{1}{z}} = \lim_{z \to

0} \frac{3z+1}{2z-1} = -1$.

We then began looking at bilinear transformations.

(note: A more thorough explanation of these transformations can be found on Section 8.10 pg 245 of our text.)

A bilinear transformation is defined as $w = f(z) = \frac{\alpha

z+\beta}{\gamma z+\delta}$ with $\alpha\delta - \beta\gamma \neq 0$

Observe that the transformation is a combination of rotation, translation, stretching, and inversion.

If $z_1$ through $z_4$ are distinct points in the $z$ plane, then

$\frac{(z_4 - z_1)(z_2 - z_3)}{(z_2 - z_1)(z_4 - z_3)}$ is invariant

under the mapping.

(note: invariant means that transformation by $w$ results in the same complex number).

We then looked at some of the properties of this bilinear transformation

as layed out by the solutions to solved problems 8.14 and 8.15 in our

text.

The inversion transformation (factor) changes a circle to either a circle or a

line if a $z$ plane circle passes through a point where the denominator

is zero.

Ex. A circle passing through $(2,0)$ [ such as $|z-1|

= 1$ ] will be transformed by the bilininear transformation

$w=(z) = \frac{3+z}{2-z}$ into a line.

A point in the interior of a circle that has $(2,0)$ in its interior in

the $z$ plane will be sent to the exterior of the transformed circle in

the $w$ plane.

3-13

For a more detailed approach to today's lecture read the section

"Projective Matrix Representations" at the Mobius Transformation

wikipedia page. The link can be found on moodle.

Homogeneous Coordinates - A 2 dimensional (column) vector can represent a real number.

[Think of fractions as ordered pairs.]

Examples:

$\frac 34 = \left( \begin{array}{cc}3 \\ 4

\end{array} \right) \tilde \left( \begin{array}{cc} \frac 34 \\ 1 \end{array} \right)$

$\frac 78 = \left( \begin{array}{cc}7 \\ 8

\end{array} \right) \tilde \left( \begin{array}{cc} \frac 78 \\ 1 \end{array} \right)$

$ a = \left( \begin{array}{cc}a \\ 1

\end{array} \right) \tilde \left( \begin{array}{cc} ta \\ t \end{array} \right)$

Comment: There is a similar approach for

complex numbers as ordered pairs of real numbers represented as 3

dimensional column vectors.

$ ( 3,4) = \left( \begin{array}{cc}3 \\ 4 \\1

\end{array} \right) \tilde \left( \begin{array}{cc} 6 \\

8 \\ 2 \end{array} \right) \tilde \left(

\begin{array}{cc} 3t \\ 4t \\ t \end{array} \right)$

An ordinary complex number can be represented likewise as a 2 dimensional vector:

$ \left( \begin{array}{cc}a \\ b

\end{array} \right) \tilde \left( \begin{array}{cc} \frac ab\\

1 \end{array} \right)$ as long as $b \ne 0$, but if $ b =0$ then

$ \left( \begin{array}{cc}a \\ 0

\end{array} \right) $ corresponds to $\infty$.

Bilinear Transformations as matrix multiplication:

Consider

$w = f(z) = \frac{\alpha z+\beta}{\gamma z+\delta}$ and the matrix : $T =

\left( \begin{array}{cc} \alpha & \beta \\ \gamma

& \delta

\end{array} \right)$.

Then $ \left( \begin{array}{cc} \alpha & \beta \\

\gamma

& \delta

\end{array} \right)$ $ \left( \begin{array}{cc} z \\ 1

\end{array} \right) = $$ \left( \begin{array}{cc}\alpha z+\beta

\\ \gamma z+\delta \end{array} \right) $ $\tilde

\left( \begin{array}{cc}\frac{\alpha z+\beta}{\gamma z+\delta} \\

1 \end{array} \right)$

The determinant of the matrix $ \left|

\begin{array}{cc}\alpha & \beta \\\gamma

& \delta

\end{array} \right| ≠ 0$ by assumption, thus the matrix is nvertible and

its inverse matrix represents its inverse bilinear trasnformation.

Note: $\det(T^{-1}) = \frac 1{\det(T)} \ne 0$.

Note that with this representation we can see that the

transformation with matrix $T$ is the same transformation as that

represented by the matrix $\alpha T$ where $ \alpha ≠ 0$ since $(\alpha

T)v = \alpha(Tv) ~ Tv$.

What happens at infinity?

Example: $w = f(z) = \frac{3 z+5}{-i z+ 2i}$ with matrix $T = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 3 & 5\\ -i

& 2i

\end{array} \right)$:

Then $ \left( \begin{array}{cc}3 & 5\\ -i

& 2i

\end{array} \right)$ $ \left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 \\ 0 \end{array}

\right) = $$ \left( \begin{array}{cc}3 \\ -i \end{array} \right) $ $\tilde \left(

\begin{array}{cc}\frac{3}{-i} \\ 1

\end{array} \right) $, so $f(\infty) = 3i$.

This is consistent with $\lim_{z \to \infty} \frac{3 z+5}{-i z+ 2i} = \frac 3{-i}$

Examples:

A simple (linear) example: $T$ such that $T(0) = 3, T(1) = i, T(\infty) = \infty$

$ \left( \begin{array}{cc} \alpha & \beta \\

\gamma

& \delta

\end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{cc}0 & 1 & 1\\ 1

& 1 & 0

\end{array} \right) =

\left( \begin{array}{cc} \beta & \alpha+\beta &

\alpha\\ \delta & \gamma+\delta & \gamma

\end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{cc}3t & iu & 1s\\ t

& u & 0

\end{array} \right) $

The equality of these matrices implies $\beta = 3t, \delta = t \alpha =

s$ and $\gamma = 0$. AND so $s+3t=iu, t=u$, and thus

$s=(i-3)t$

Thus $ \left( \begin{array}{cc} \alpha & \beta \\

\gamma

& \delta

\end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{cc}s & 3t \\0

& t

\end{array} \right)= \left( \begin{array}{cc}(i-3)t & 3t \\0

& t

\end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{cc}i-3 & 3\\0

& 1

\end{array} \right)$. Thus $T(z) = (i-3)z +3$ or $T: z \to w= (i-3)z + 3$

Comment: Here, Since $T$ is linear in this example, $\gamma = 0$. If

$\gamma ≠ 0$ then all coefficients can be divided by $\gamma$, [so we

can assume $\gamma = 1$ andand the pole will be at

$-\delta/\gamma$ instead of at $\infty$

Example: Consider a bilinear transformation $T$ such that $T(0) = 1, T(1) = -i, T(i) = 3$.

$ \left( \begin{array}{cc} \alpha & \beta \\ \gamma

& \delta

\end{array} \right)$ $ \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 & i \\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{array}

\right) =\left( \begin{array}{cc} \beta & \alpha+\beta &

\alpha i + \beta\\ \delta & \gamma+\delta & \gamma i +\delta

\end{array} \right) = $ $ \left( \begin{array}{cc}\ t & -iu & 3v \\ t & u& v \end{array} \right) $

So here are some immediate consequences of this matrix equation that can

lead to solving for a matrix representative of $T$: [6 linear equations

in 7 unknowns.]

$ \beta=t, \delta=t; \beta=\delta$;

$\alpha i+\beta=3v, \gamma i+\delta=v; \alpha

i+\beta=3(\gamma i+\delta)$

$ \alpha+\beta=-iu,

\gamma+\delta=u; \alpha+\beta=-i(\gamma+\delta)$

Solving these equations can be done using linear algebra..

3-23: The Definition of the line integral for complex functions.

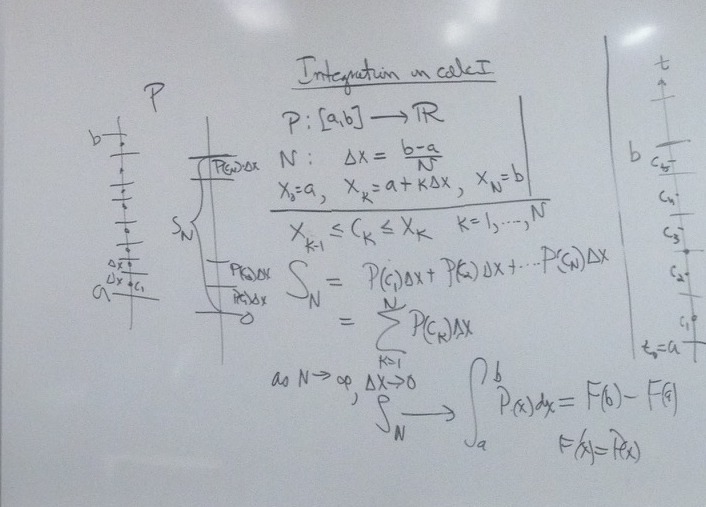

Recall the definition of the integral for real valued functions from beginning calculus:

Suppose $P: [a,b]\to (-\infty. \infty)$. Let $N \gt 0$ be a

natural number and $\Delta x=\frac {b-a}N$ so that

$x_0=a, x_k=a+k\Delta x, x_N=b$; and $x_{k-1}

\le c_k

\le

x_k,

k=1,2,3,... N$.

We let $S_N=P(c_1)\Delta

x+P(c_2)\Delta

x+...+P(c_N)\Delta x = \sum_{k=1}^N P(c_k)\Delta x$.

So that as $N \to \infty$ and $\Delta x \to 0$, we have

$S_N \to \int_a^b P(x)dx = F(b) - F(a)$ where $F'(x) =P(x)$.

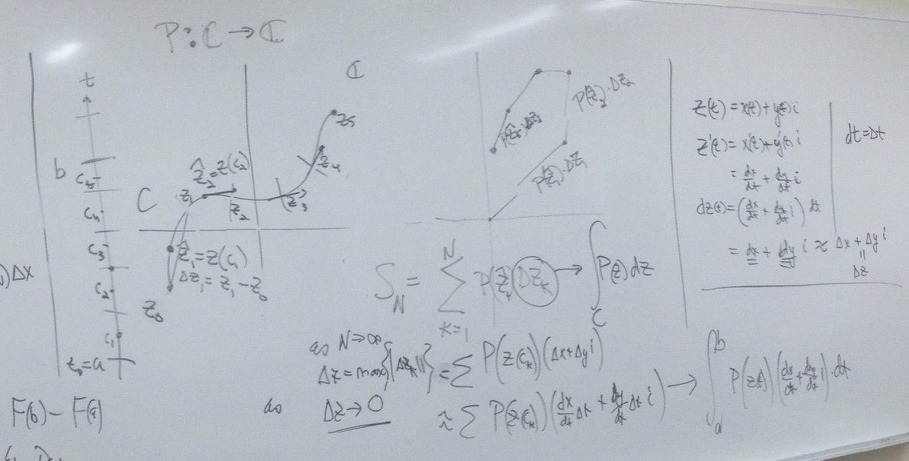

We have a comparable definition for the line integral of a complex

function $P: \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}$ over a curve $C$ parametrized by

the function $\gamma = z: [a,b] \to \mathbb{C}$.

Let $N \gt 0$ be a natural number and $\Delta t=\frac {b-a}N$ so that

$t_0=a, t_k=a+k\Delta t, t_N=b$; $t_{k-1}

≤ t_k

≤ t_k$, AND $\Delta z_k = z (t_k) - z (t_{k-1})$ for $k=1,2,3,... N$

We let $S_N=P( z (c_1))\Delta z_1+P( z (c_2))\Delta z_2+...+ P( z

(c_N))\Delta z_N \\ = \sum_{k=1}^N P( z (c_k))\Delta z_k$

So that as $N \to \infty$ and $\Delta z_k \to 0$, and we have

$S_N \to \int_C P(z)dz = \int_a^b P( z(t)) z '(t) dt$.

E.g. $w=P(z)=z^2$ $C: z(t)=t+2ti, 0≤ t ≤1

$ $C$ is a line segment from $z=0$ to $z=1+2i$. $x9t) = t; y(t) = 2t$ so $\frac {dx}{dt} = 1 $ and $\frac{dy}{dt} = 2$.

$\int_C z^2 dz = \int_0^1 z(t)^2 (1+ 2i) dt = \int_0^1 (t+2ti)^2 (1+ 2i)

dt = (1+2i) \int_0^1 t^2-4t^2 +4t^2i dt \\ = (1+2i) \int_0^1 t^2(

-3 +4i) dt \\ = (1+2i) (-3+4i) \frac{t^3}3 |_0^1 \\ = \frac13

(1+2i)(-3+4i) -0 = \frac 13 (1+2i)^3$.

Fun facts: $\int_{-C} P(z)dz

= −\int_C P(z)dz $ and $\int_C (\alpha P(z)

+ Q(z))dz = \alpha \int_C P(z)dz + \int _C Q(z)dz$.

3-25

SOS Problem 8.80. Find a bilinear transformation that maps the circle $|z – 1|= 2$ onto the line $ x + y =1$.

Solution:

Step 1. Understanding the problem: For a bilinear transformation $w=T(z)$ : circle $\to$ circle or line.

A bilinear transformation is determined by the images of 3 points.

Step 2: Plan: Take 3 points on circle and assign them to 3 points

on line : use that to determine a bilinear transformation that

accomplishes the desired result.

Step 3: Execute plan: 3 points on the circle: $z_1= 3, z_2=-1, z_3 = 1+2i. w_1=1 , w_2=i, w_3=2-i$.

Side work to find transformation:

Method A. Since this transformation must involve inversion to take a

circle to a line, Solve simultaneous equations for $T$ with $\delta=1$.

Method B. Use the invariance of the cross ratio: $\frac

{(w-w_1)(w_2-w_3)}{(w-w_3)(w_2-w_1)}= \frac

{(z-z_1)(z_2-z_3)}{(z-z_3)(z_2-z_1)} \\

\frac {(w-1)(i-(2-i))}{(w-(2-i))(i-1)}= \frac {(z-3)(-1-(1+2i))}{(z-(1+2i))(-1-3)} \\

\frac{(w-1)2}{(w-2+i))}=\frac {(z-3)(1+i))}{(z-1-2i))(2)}$

New equation from cross multiplying: $4(w-1)( z-1-2i)=(z-3)(1+i) (w-2+i) $

Collect w terms on one side of equation: $ w(4z-4-8i)-w(z(1+i)-3(1+i))= 4(z-1-2i) +(z-3)(1+i)(-2+i)$

$w*[(4z-4-8i)-z(1+i)+3(1+i)]= 4(z-1-2i) +(z-3)(1+i)(-2+i)$

So $w = \frac{4(z-1-2i) +(z-3)(1+i)(-2+i)}{(4z-4-8i)-z(1+i)+3(1+i)}$. Simplify to obtain the desired transformation.

3-27 [Draft] Part of these notes are taken from Module for The

Cauchy-Goursat Theorem

A closed curve has the property γ(a)=γ(b) and a simple curve has the

property $\gamma(t) \ne \gamma(s)$; for $ s \ne t$ except when

$\{s,t\}=\{a,b\}$.

Jordan Curve Theorem: For a closed, simple curve, a point not on the curve is either inside or outside the curve.

Let the simple closed contour C

have the parametrization $C: z(t) = x(t) + y(t) i$ for $a \le t \le b$. Recall

that if $C$ is parametrized so that the

interior of $C$ is kept on the left as

4z(t)$ moves

around $C$, then we say that

$C$ is oriented positively

(counterclockwise); otherwise, $C$ is

oriented negatively (clockwise).

If $C$

is positively oriented, then $-C$ is

negatively oriented. The figure below illustrates the concept

of positive and negative orientation.

Fact: If the point is inside the curve and you draw a line from the point to what is clearly outside the curve,

then the line will cross the curve an odd number of times. If the point is outside the curve and

you draw a line from the point to what is clearly outside the curve, then the line will cross the

curve an even number of times.

If you have an annulus and want to integrate over the boundary

curve, orient the inside circle in the direction opposite of

the outside circle.

3-30 More to come: Key ideas for the Cauchy Goursat Theorem.

A

domain D is said to be a simply

connected domain if the interior of any simple closed contour

C contained in D

is contained in D. In

other words, there are no "holes" in a simply connected

domain. A domain that is not simply connected is said to

be a multiply connected domain. Figure 6.16 illustrates

uses of the terms simply connected and multiply connected.

4-1 Review of materials on Quiz 3.

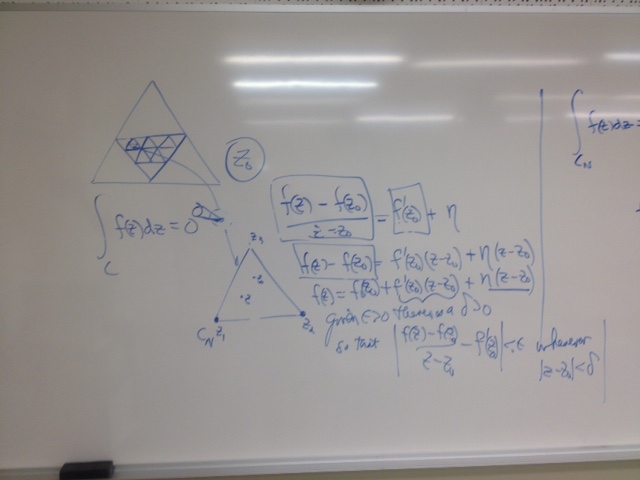

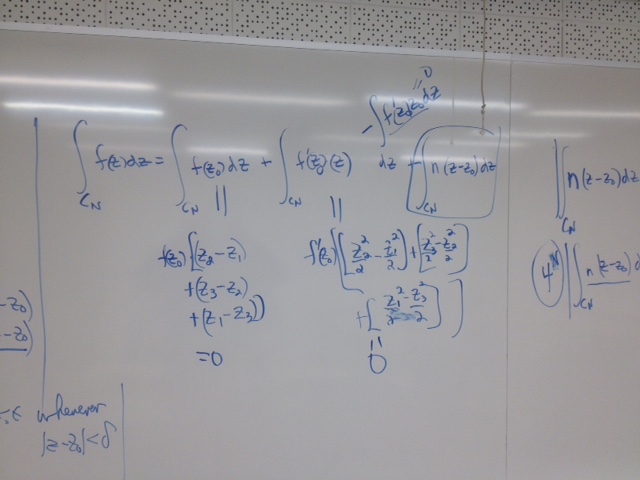

4-3 Completion of proof of Cauchy's Theorem for a triangle. [Start of Applications of CT].

See SOS for fundamental outline of argument.

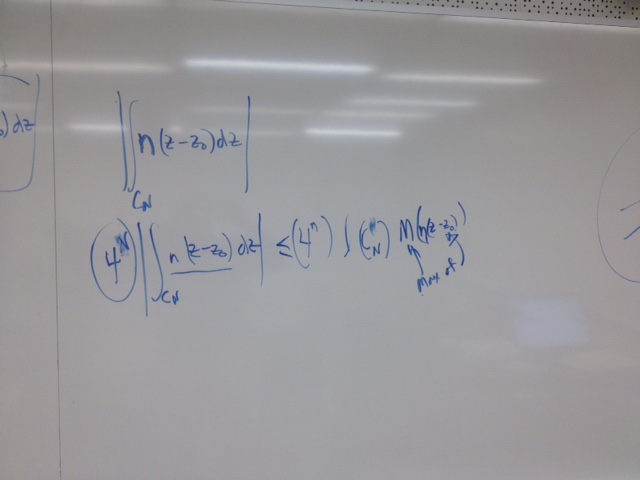

We have found a nested sequence of similar triangles $\Delta_k$

with $|\int_{\Delta}f(z) dz| \lt 4^n|\int_{\Delta_n}f(z) dz|$.

We also have located a number $z_0$ where $z_0 \in \Delta_k$ for all $k$.

Since $f$ is analytic on a domain that contains $z_0$, $\lim_{z \to z_0}\frac {f(z)-f(z_0)}{z-z_0} = f'(z_0)$.

Rephrasing this in terms of $\epsilon's$ and $\delta's$, we have that:

Given $\epsilon \gt 0$ there is a $\delta \gt 0$ so that

$\frac {f(z)-f(z_0)}{z-z_0} - f'(z_0) =\eta \lt \epsilon$ whenever $|z-z_0| \lt \delta$.

Thus for $n$ large enough, $f(z)= f(z_0) + f'(z_0)(z-z_0) + \eta (z-z_0)$, so

$\int_{\Delta_n}f(z) dz = \int_{\Delta_n}f(z_0)dz + \int_{\Delta_n}f'(z_0)(z-z_0)dz + \int_{\Delta_n}\eta (z-z_0) dz$.

But $\int_{\Delta_n}f(z_0)dz = 0$ and $ \int_{\Delta_n}f'(z_0)(z-z_0)dz =0$.

So our attention turns to

$\int_{\Delta_n}\eta (z-z_0) dz$

Turning to the comparison of the modulus of the integral property we have

$|\int_{\Delta_n}\eta (z-z_0) dz| \le l(\Delta_n) * M$ where $M= max(\eta |z-z_0|)$ on $\Delta_n$.

But on $\Delta_n$, $|z-z_0| \lt \frac {l(\Delta) }{2^n}$,

$l(\Delta_n) \lt \frac {l(\Delta) }{2^n}$, and $\eta \lt

\epsilon$.

So we conclude that for $n$ large enough,

$|\int_{\Delta}f(z) dz| \lt 4^n|\int_{\Delta_n}f(z) dz| \lt 4^n

|\int_{\Delta_n}\eta (z-z_0) dz| \le 4^n*l(\Delta_n) * M \lt 4^n

\epsilon \frac {l(\Delta) }{2^n}\frac {l(\Delta) }{2^n} \lt \epsilon

l(\delta)^2 $.

Thus $|\int_{\Delta}f(z) dz| $is smaller than any positive real number, so $\int_{\Delta}f(z) dz =0.$

Week 11 Notes - still in draft form- more details may appear in the future.

Monday April 6:

Monday April 6th, 2015

Today, we initiated lecture by going over Cauchy's Integral Formula

(5.1) as stated on page 144 of our Schaum's Outlines Complex Variables

text.

A slight manipulation of (5.1) yields:

$\oint\limits_C\frac{f(z)}{z-a}dz=f(a)2\pi i$

which we became familiar with by looking at simple applications such as:

$(1)\oint\limits_{|z|=1}\frac{1}{z}dz=f(0)2\pi i=2\pi i$

where $f(z)=1$ for all $z$ and $a = 0$.

Similarly:

(2)$\oint\limits_{|z-i|=1}\frac{z^{2}+5z+3}{z-i}dz=2\pi i$

(3)$\oint\limits_{|z-1|=1}\frac{z^{2}+5z+3}{z-i}dz=\pi (2+5i)$

(4)$\oint\limits_{|z|=2}\frac{z^{2}+5z+3}{z^{2}+1}dz=

\oint\limits_{|z|=2}\frac{z^{2}+5z+3}{(z+i)(z-i)}dz$

$=\oint\limits_{|z-i|=1}\frac{z^{2}+5z=3}{(z+i)(z-i)}dz+

\oint\limits_{|z+i|=1}\frac{z^{2}+5z=3}{(z+i)(z-i)}dz$

=$\pi(2+5i)-\pi(2-5i)=10\pi i$

At this point we made the observation that finding complex integrals is easier than finding real integrals.

Section 5.2 of our Schaum's Outline's Complex Variables text lays out

all of the important consequences of Cauchy's Integral Formulas, one of

which includes The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, which we get into

later in the week.

Wednesday April 8th, 2015

This week we have been working on complex integration using Cauchy's Integral Formulas.

We began lecture by looking at exercise 5.32 b) in our Complex Variable text. The problem statement is given as follows:

(1) Evaluate $\oint\limits_C\frac{e^{3z}}{z-\pi i}dz$ if $C$ is the ellipse $|z-2|+|z+2|=6$.

Our immediate goal was to verify whether $\pi i$ was on our ellipse or

not. A quick check using sample point $3i$ reveals that $\pi i$ is

outside of our ellipse since $3i$ is outside of our ellipse. Thus by

Cauchy's Theorem, $\oint\limits_C\frac{e^{3z}}{z-\pi i}dz=0$

since $\frac{e^{3z}}{z-\pi i}$ is analytic on our curve $C$.

We also looked at exercise 5.35 which asks to:

(2) Evaluate $\oint\limits_C\frac{e^{iz}}{z^{3}}dz$ where $C$ is the circle $|z|=2$.

A quick use of Cauchy's Integral Formula (5.2) with $a=0$ and $n=2$ will give us our solution (as the reader should verify).

Similarly,

(3)$\oint\limits_{|z|=1}\frac{cos(z)}{z^{3}}dz=\frac{2\pi i}{2i}f''(0)=-\pi i$ using (5.2).

We ended the lecture by looking at the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

and how the factor theorem is a consequence of the division algorithm.

In the context of real numbers , polynomials with real coefficients

factor into a product of linear factors and irreducible quadratic

factors.

Friday April 10th, 2015.

Today we looked viewed a video of a 9 year old boy prove The Fundamental

Theorem of Algebra in various ways. We attempted to catch flaws in his

reasoning, but failed. See the video at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnUnkr3shDg

04-13: Sequences and Series

- In the complex plane sequences are not tied down to the real line and have much more freedom.

- Given

$\epsilon > 0$ if there exists $N$ such that if $k>N$, then $|z_k - L|

< \epsilon$, then we say $\lim _{n \to \infty} z_n = L$.

- $(-1)^n$ alternates between $0$ and $1$, hence diverges.

- Same is true about $i^n$ , but alternates between $1 , i , -1 ,$ and $- i$.

- $(1/2)^n : 1 , 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, ... \to 0$.

- In the complex plane $(1/2i)^n : 1, 1/2i, -1/4, -1/8i, ....$ but still goes to $0$.

- If there exists a limit, then the limit is unique.

- $lim_{n \to \infty} Z_n = L$ iff $lim_{n \to \infty} Z_n -L = 0$ iff $lim_{n \to \infty} |Z_n -L| = 0$

- In the real numbers, $r^n \to 0$ if $-1 < r < 1$, $\to $ if $r=1$, and diverges if $r \le -1$ or $r>1$.

- In the complex numbers, $z^n \to 0$ if $|z|<1$, $\to 1$ if $z=1$, and diverges if $|z| \ge1, z \ne 1$.

04-15:

- If $|z|=1$ and $Arg(z)$ is a rational multiple of $\pi$

then the sequence $z^n$ cycles as it goes around and around the unit

circle.

- We looked at sequences in the complex plane using GeoGebra.

- If $|z|=1$ and $Arg(z)$ is an irrational multiple of $\pi$ the

sequence $z^n$ gets close to whatever we want (dense) on the unit

circle.

- If $|z|>1$, then the sequence $z^n$ is getting farther away from any point.

- Geometric series in complex plane discussed briefly.

04-17:

- Looked at various series on GeoGebra.

- Every bounded sequence of complex numbers has a convergent subsequence (a consequence of compactness).

- The

ratio test works in the complex plane for complex series. The series

convergence will be absolute convergence- which inplies convergence of

the series.

- The

Taylor series: $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} f ^{n}(0) \frac{z^n}{n!}= f(x)$ ,

Theorem: Whenever the Taylor series converges, it will converge to the

original function.

4-20

Looking at $f(z) = \frac {e^z}{z^5}$, we have a pole of order 5 at the origin, because $z^5 f(z)$ is analytic at $z=0$.

$f(z) = e^{1/z}$ has an isolated essential singularity at the origin

becauseany power of z, $z^n f(z)$, still has a singularity at $z=0$.

$f(z)=\frac{\sin(z)}z$ has a removable singularity. (just like on the real number function $f(x)=\frac{\sin(x)}x$).

$ f(z) = \frac1{1-z}$ has a simple pole when $z=1$.

Taylor's Theorem (for polynomial approximations) was proved, can be seen in

our textbook.

We noted that the remainder of $f(z) -T_n(z)$ can be calculated by

bounding the largest magnitude of $w = f(z)$ on the circle times the circumference of the circle.

We

also noted that the Cauchy Integral Formula doesn’t apply to the real numbers,

only complex numbers.

Problem 6.37 was looked at . The first term is $\frac 12$ and the

ratio between successive terms was noted to be $\frac z2$ , so using the geometric series

formula, we calculated that the series converges to $\frac1{2-z}$.

Factoring out a $\frac 1z$ from the entire series, we have that the

series converges if the magnitude $|2z| \lt 1$. Solving for $z$, we have that

the magnitude has to be less than $\frac 12$, and so the series converges to the

product $\frac1z \cdot \frac 1{2z-1}$.

4-22

We started the day with showing that the $\tan(z)$ can be

expressed as a set of taylor polynomials for $|z| \lt \frac{\pi}2$.

The trick to solve this problem is to take multiple

derivatives, and using Taylors theorem to expand this to order 7. Wolfram alpha

can be used to check the work.

When looking at $f(z)= e^z$ and at its expansion about $z=1$, we noted that

plugging $1$ for $z$ gave us the

polynomial $e+e(z-1)+e\frac{(z-1)^2}{2!}+...+e\frac{(z-1)^n}{n!} + ...$ And so on and so on.

The next example we looked at was $f(z)= \frac {e^z} {z^3}$. This function

has a pole of order 3 at the origin for obvious reasons. Now in order to relate

this function to an analytic function, we multiply it by $z^3$ which gets rid of the problem at the origin

and makes it nice.

We first write $f(z)$ out as a Laurent Series by factoring out a

$\frac 1{z^3}$ from $e^z$. This gives the Laurent series:

$f(z)= \frac 1{z^3} (1 + z + \frac {z^2}{2!} + ...+\frac{z^n}{n!} + ... =

\frac 1{z^3} + \frac 1{z^2} + \frac 1{z 2!} +

...+\frac{z^{n-3}}{n!} + ... $

Looking at example 6.91, we are asked to give $\frac1{z-3}$ in a Laurent

Series Valid for $|z|<3$.

We first factor out a $\frac{-1}3$ from the function to give us a

form we can work with. Letting $u =\frac z3$, we have the function $f(z) = \frac {-1/3}{1-u}$.

Writing out the series, we show that it converges for values of magnitudes $|z| \lt 3$.

For magnitudes $|z| \gt 3$, turns out, you flip all

the

terms, $\frac1{z-3} = \frac1{1-3/z}$, then expand with geometric series

which will converge when $|\frac 3z| \lt 1$ or $|z| \gt 3$ and the

truth holds.

Problem 6.92, we want to expand $\frac z{(z-1)(2-z)}$. Using partial

fractions , we found $A=1$ and $B=2$, so$\frac z{(z-1)(2-z)} =

\frac 1{z-1} + \frac 2{2-z}$

.

(a) for $|z| \lt 1$: Writing each term as an its own series, we get that

the series is the sum from $\sum_0^{\infty}(-1 +\frac1{2^n})z^n$.

(b) For part two of the problem, $ 1 \lt |z| \lt 2$, the B term is

good, but the first part must be made into a Laurent Series, and therefore

"flipped" as in 6.91.

4-24

We talked about uniform continuity.

In general, uniform continuous implies continuous, but the converse usually doesn’t hold.

What it means for a function

to be uniformly continuous is that for every $\epsilon

>0$ there exists a $\delta >0 $ such that $|z-c|< \delta$

implies $|f(z)-a|<\epsilon$ for any $c$ in the domain of $f$. Meaning

that we

just can use one delta for the whole domain of the function with the

limiting values of the function falling

uniformly within the given epsilon bound.

We discussed a Theorem; If f is restricted to a

compact set, then

f being continuous implies uniform continuity, So for a bounded domain, a

continous functon is uniformly continuous for any closed subset. And so

COMPACTNESS => {Continuity =>UNIFORM CONTINUITY}.

A key example from real variable functions is $f(x) = \frac 1x$ where

the function is continuous for $(0,1)$, but not uniformly continuous. When

$a$ is close to $0$ the choice of $\delta$ requires them to be smaller

because the magnitudes in $\frac 1x$ becomes larger.

Consider the function $\frac1z$. This function is has an isolated singularity at

the origin, so it can’t be uniform continuous for a domain containing $0$.

Consider the same function but with the

restricted domain of $|z| \ge 1$. Because now we can restrict how big our y

values get, we get uniform continuity on this domiain.

4-27

Went over assigned problem 4.78 - ∫C1 ((z2+2z+5)/(z2+4)(z2+2z+2)) dz; C1={z: |z|=R}

Roots are 2i, -2i, -1+i and -1-i

a) As R grows it eventually contains all four of these poles, so integrate around each

Ex: g1(z) = (z2+2z+5)/((z+2i)(z2+2z+2))

Do Laurent series around 2i: ∫ (g1(2i)/(z-2i)) + g1'(2i)(z-2i)/(z-2i) + …

Every derivative of g1 is analytic, so all become 0. Then

∫ (g1(2i)/(z-2i)) = g1(2i)*2πi, called the residue of f at 2i

b) |z-2|=5 contains all poles, so by part a the integral will be 0; a

larger circle of radius R will eventually

contain |z-2|=5, so its integral will be the same

c) The integral of |z+1|=2 is the sum of the two residues at -1+i and

-1-i, so that sum must be 0 for the integral to

be 0

Different way to do part a: z = Reiϴ, dz = iReiϴdϴ

∫2π 0 ((R2ei2ϴ+2Reiϴ-5)/(R2ei2ϴ+4)( R2ei2ϴ+2Reiϴ+2))iReiϴdϴ

|(R3(ei2ϴ+(2eiϴ/R2)-(5/R3))/(R2(ei2ϴ+(4/R2))*R2(ei2ϴ+(2eiϴ/R)+(2/R2)))|

= 1/R |(ei2ϴ+(2eiϴ/R2)-(5/R3))/((ei2ϴ+(4/R2))*(ei2ϴ+(2eiϴ/R)+(2/R2))) ≤ M/R

since the bounded terms fall out as R goes to infinity

|∫C f(z)dz| ≤ (M/R)*2π, which goes to 0 as R goes to infinity, thus the integral goes to 0

Note: it is very important that the degree of the denominator be 2 or more than that of the numerator

4-29

Real number integral of (1/(1+x2))dx evaluates to π using arctan. Now we do so using residues:

1/(1+z2) has poles at i and -i, so

∫C (1/(1+z2))dz = ∫C (1/(z+i))*(1/(z-i)))dz = 2πi(1/i+i) = 2πi(1/2i) = π

where (1/i+i) is the residue at i

For any R, assuming R > 1, we evaluate in two parts:

ɤ1(t) = -R+t from 0 ≤ t ≤ 2R ɤ2(t) = Reit from 0 ≤ t ≤ π

So, for ɤ1 the integral is

∫2R 0 (1/(1+(-R+t)2))dt

For x = -R+t, the integral is then

∫x=R x=-R (1/(1+x2))dx = π - ∫ɤ2 (1/(1+z2))dz

The integral of ɤ2 must go to 0, as follows:

|∫t=π t=0 (1/(1+ Reit)2) iReitdt| ≤ ∫t=π t=0 |(1/(1+ R2ei2t))*R| dt

The magnitude function is

R/(1+ R2ei2t) = (R/R2)/(1/R2 + ei2t)) = (1/R)/(1/R2 + ei2t))

R going to infinity makes this function 0, so the integral will become 0 as well.

4-29: More to come.

$C_2: \gamma_2(t)=Re^{it}$ with $0 \le t \le \pi$.

Outline for showing $\lim_{R\to \infty}\int_{C_2} \frac 1{1+z^2} dz =0$.

Assume $R \gt 1$.

$|\int_{C_2} \frac 1{1+z^2} dz| = |\int_0^\pi \frac 1{1+R^2e^{2ti}}

Rie^{it}dt| \le \pi \ max\{ |\frac 1{1+R^2e^{2ti}}| \cdot R\}$.

Note that on $C_2$, $|1-R^2| \le |1+R^2e^{2ti}| $ so

$|\frac R {1-R^2}| \gt |\frac 1{1+R^2e^{2ti}}| \cdot R\}$.

So $|\int_{C_2} \frac 1{1+z^2} dz| \le \pi | \frac R {1-R^2}|$ .

As $R \to \infty$, we have $\frac R {1-R^2}\to 0$, so we conclude $\lim_{R\to \infty}\int_{C_2} \frac 1{1+z^2} dz =0$.

5-01

Continued from 4-29:

|∫t=π t=0 (1/(1+ Reit)2) iReitdt| ≤ π*max(|R/(1+ R2ei2t)|)

Assuming R>1, the maximum value of this function is found as the denominator goes to 0, so

0 < |1-R2| ≤ |1+ R2ei2t|

R/|1-R2| ≥ R/|1+ R2ei2t|

Then the above function is π*(R/|1-R2|), which goes to 0 as R goes to infinity

Analytic Continuation: a function defined by a series always has an

analytic continuation (another function defined by a series that is

analytic on first function's boundary) on its boundary

Ex: 1+x+x2+ … = 1/(1-x), for |x|<1 has an analytic continuation 1+z+z2+ … = 1/(1-z), for |z|<1