We have already explored one model for learning in which the

learning

rate was a positive decreasing function of time, i.e. $ L'(t) = \frac 1t$. The

solution to this model with the initial condition $L(1) = 0$ led us to

the

natural logarithm and a model for learning that had the values of $L(t)$

unbounded in the sense that for any number $B$ there was some $t$ where

$L(t)

> B$. Although this model is very encouraging in terms of the

unbounded

increase in learning, it does not match very well with much experience.

In many situations there are bounds to what can be learned no matter

how

much time is spent in the process. In trying to find a model for such a

learning curve, we examine a similar rate of learning that is positive

but less than $\frac 1t$.

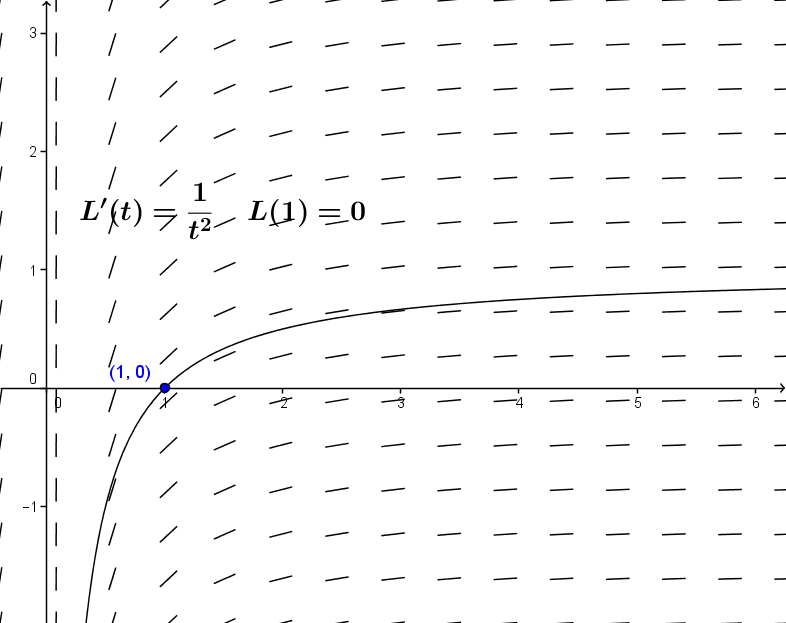

Example VI.D. 1. Suppose $L_2'(t)= \frac 1{t^2}$ and $L(1) = 0$. Find $L_2(2)$ and discuss the value of $L_2(t)$ when $t > > 0$.

Solution: This problem is not too hard since $G(t) = \frac {-1}t$ has

$G'(t)= \frac 1{t^2}$. Thus $L_2(t) = \frac{-1}t + C$. Solving for

$C$ we use $0 = L_2(1) = -1 + C$ so $C = 1$ and

$L_2(t) = 1 - \frac 1t$ for all $t > 0$.

To respond to the problem, we have $L_2(2) = 1 - \frac12 = \frac 12$

.When $t > > 0$ then $L_2(t)$ is close to $1$.

Comment:

We

now have a model for learning with bounded growth. At this stage we'll

modify the differential equation just slightly and consider the same

questions

for a derivative function for which we do not yet have an

antiderivative.

Solution:

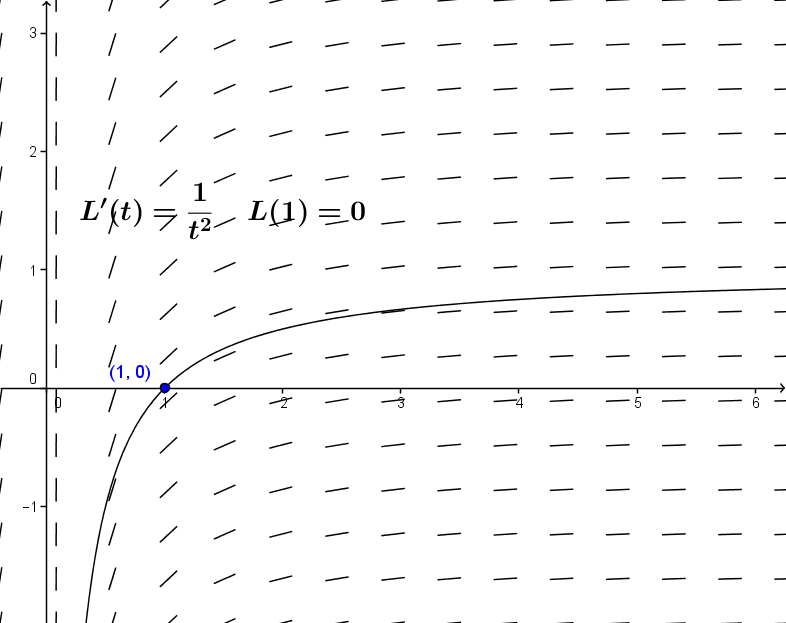

At this stage we have no elementary function which

has $\frac 1{1+t^2}$ for its derivative.

Looking at the tangent

field

and a sketch of the integral curve for this differential equation gives

some idea of the shape of the solution. [See Figure VI.D.2]

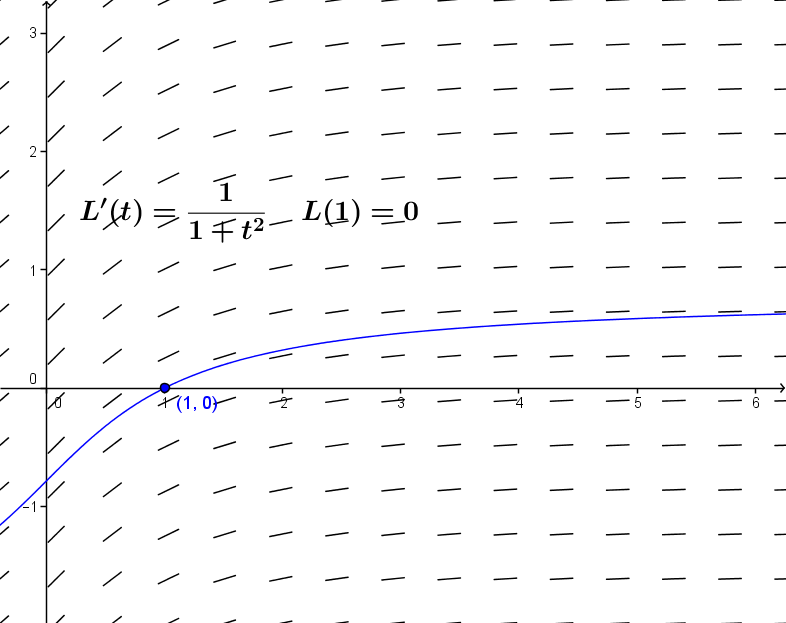

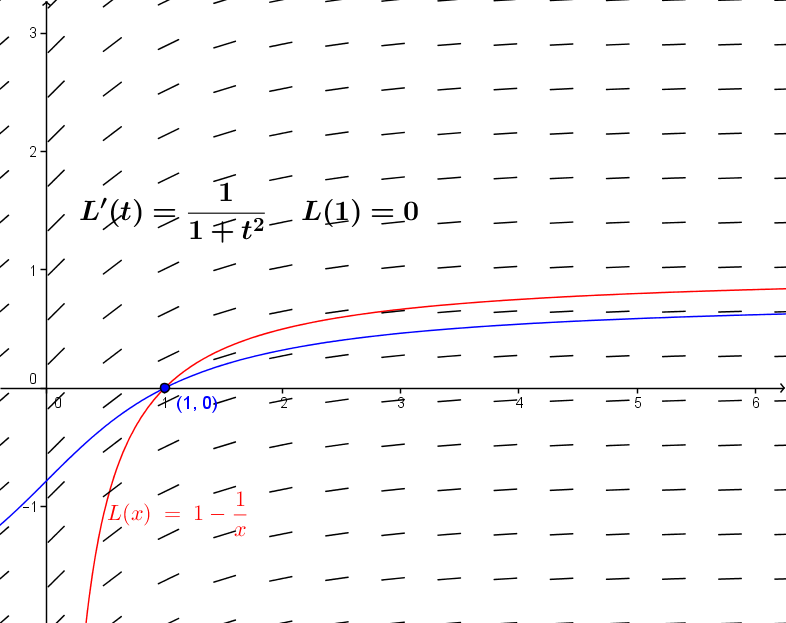

We consider $A'(t)$ and $L_2'(t)$ as the rates at which the

amount

learned is changing.

Then since $\frac 1{1 + t^2} < \frac 1{t^2}$ for any $t >

1$, the amount learned at any time $t$ according to the $L_2(t)$

model is larger than that learned according to the $A(t)$ model. [See

Figure

VI.D.3.]

$A(t)$ is increasing for all $t$, yet since $0 = A(1) = L_2(1)$

and as $t$ gets large, $L_2(t) \rightarrow 1$,

it must be that $A(t) < L_2(t) < 1$ for all $t$ .

By careful analysis of this situation it should seem reasonable that

as $t$ gets large, $A(t)$ approaches some

specific

number that is at most $1$.

Later this section we will see what this

number

is, but for now we continue our analysis to try to find $A(2)$.

First, as we did with the model for L(t), we can estimate A(2) using

Euler's method.[Can you explain why this is an overestimate?]

| t | A | A'(t)=1/(t2+1) | dA=A'(t)*dt |

| 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.125 |

| 1.25 | 0.125 | 0.390243902 | 0.097560976 |

| 1.50 | 0.222560976 | 0.307692308 | 0.076923077 |

| 1.75 | 0.299484053 | 0.246153846 | 0.061538462 |

| 2.00 | 0.361022514 | 0.2 | 0.05 |

This is easy enough in theory because of the fundamental theorem of calculus, but it doesn't express the funtion A as any elementary function that we have studied yet in the calculus.

To develop this differential equation further we introduce a slight variation on the function A, changing the initial condition of the differential equation to arrive at a more enlightening solution.

Suppose A 0'(t) = 1/(1+t 2) and A 0(0) = 0. Then since A'(t) = A 0'(t) for all t, A(t) = A 0(t) + C for some constant C. We'll come back to A(t) later in this section, but now we'll focus on A 0.

To understand A 0, we look at F(x) º A 0( tan(x)). Using the chain rule and the derivative of the tangent function together with the differential equation defining A 0 we have that

Now this means that for all x in (-pi /2,pi /2), F(x) = x + K for some constant K. Evaluating F at 0, we see that F(0) = A 0( tan(0)) = A 0(0) = 0 = 0 + K, so F(x)= x for all x in (-pi /2,pi /2). This means that for these value of x, A 0(tan(x)) = x

But the function that satisfies this property is the arctangent

function.

Thus A 0(t) = arctan(t) for all t.

This result can be expressed in a more direct fashion, namely, arctan'(t)

=

1/(1+t 2).

Example VI.D.2 (continued) From the last result we have that

A(t)

= arctan(t) + C and therefore

0 = A(1) = arctan(1) + C = pi /4 + C. So

C = -pi /4 and A(t) = arctan(t) - pi

/4.

Recalling the basic properties of the arctangent function allows us to answer the original questions about A.

Derivatives of Inverse Trigonometric Functions.

At this point we'll stop a moment to give a more geometric

justification

of the result on the derivative of the arctangent. We'll use the same

technique

to find the derivative of the arcsine function, leaving the derivatives

of the arccosine and the arcsecant as exercises.

Theorem VI.D.1: For all x , arctan'(x) = 1/(1 + x 2).

Proof: Recall that tan'(t)=sec 2(t) for all t in (-pi /2,pi /2).

Recall also that the tangent function can be visualized by drawing

an

arc of length t on a unit circle to determine the point P with

coordinates

(cos(t), sin(t)), drawing the radius through P to meet the tangent line

to the circle X=1 at the point Q with coordinates (1,tan(t)). [See

Figure

VI.D.4.]

Now a change of angle, dt, gives a corresponding change in the position of Q, called dy where y=tan(t) . Then the ratio dy/dt is approximately sec 2(t) so the ratio of dt/dy is approximately 1/sec 2(t). But t is the arctan(y). Now when dy -> 0,

dt/dy -> 1/sec 2(t), so we have arctan'(y) = 1/sec 2(t) = 1/(1+tan 2(t)) = 1/(1 + y 2).

Changing the name of the variable completes the argument. EOP

Corollary VI.D.2:![]() .

.

We now turn our attention to the inverse function of the sine, called the arcsine.

Theorem VI.D.3: For x with -1 < x < 1 , arcsin'(x) = 1 / sqrt

(1-x 2).

Proof: Recall that sin'(t) = cos(t) for all t in

(-pi /2,pi /2)

.

The sine function can be visualized [See Figure VI.D.5.] by drawing

an arc of length t on a unit circle to determine the point P with

coordinates

(cos(t), sin(t)), then drawing the horizontal line through P to meet

the

vertical axis at the point S with coordinates (0,sin(t)).

Now a change of angle, dt, gives a corresponding change in the position of S, called dy where y=sin(t). Then the ratio dy/dt is approximately cos(t) so the ratio of dt/dy is approximately 1/cos(t). But t is the arcsin(y) so when dy -> 0, dt/dy -> 1/cos(t). Thus we have

Changing the name of the variable completes the argument. EOP

Corollary VI.D.4:![]() .

.

Theorem VI.D.5: For x with -1 < x < 1 , arccos'(x) = -1

/ sqrt (1-x 2).

Proof: Though a detailed proof of this result can be obtained using the derivative of the cosine (see exercise 19), the fact is most easily understood by noting that arccos(x) = p /2 - arcsin(x). EOP.

Theorem VI.D.5: For x with 1 < x or x < -1 , arcsec'(x) = 1/[ x sqrt(x 2 - 1)].

Proof: Left as an exercise.

Comments: The derivatives of functions involving the inverse

trigonometric functions are found using rules for differentiation

examined

previously in Chapter III. Applications of these functions arise in

situations

where angle measurement can be used to control some other measurement.

What is somewhat more difficult is recognizing these functions in

integration

problems. Unlike differentiation, there are no completely general

methods

for attacking integration. We will explore some further integration

methods

later, but for now here are two examples showing how substitution can

come

into play to find integrals related to the arctangent.

Example VI.D.iii. Find a) and

b)

and

b)![]() .

.

Solution: a) Let u = exp(x) so that du = exp(x) dx and this integral becomes

b) Let u = 1 + x, so that du = dx and this integral becomes

Comment: Integrals related to the arcsine function also can be complicated by substitutions and the need to recognize an appropriate choice for the substitution. In b) this meant supposing that 2 + 2x + x 2 = 1 + u 2. Solving for u we now have u 2 = 1 + 2x + x 2 = (1 + x) 2 so u = 1 + x and we can continue.

Exercises VI.D

Find derivatives for the following functions:

There are many more possible models for learning that involve positive, decreasing functions. For problems 25-30 assume that L'(t) = P(t) and L(1) = 0.